On May 4, 2023 the Asian American Christian Collaborative (AACC), which is a national organization that focuses on education/equipping, advocacy, and community building to represent the voices, issues, and histories of Asian Americans, congregated Asian American Christian leaders from all over the United States for an unprecedented Listening Session with the White House. An impressive group of people comprised this delegation, including non-profit leaders, foundation leaders, and local church pastors.

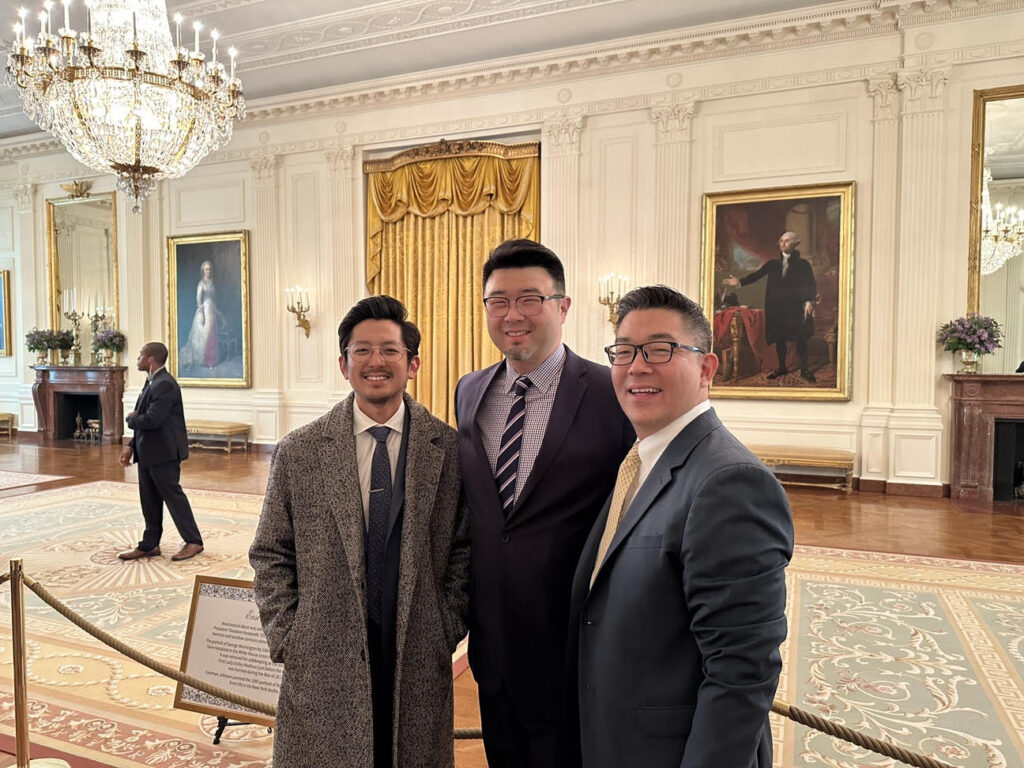

We (Peter Lim, Jason Min, and Kevin Yi) were privileged to be included in this assembly, and this is our reflection on this monumental event. We chose to express our experience in an interview format, reflecting three perspectives regarding this singular event.

1) Why did you accept the invitation to be part of the delegation to the White House Listening Session?

Peter Lim: In truth, when I received the invitation, the first thing that came to my mind was, “Why?” To be clear, I was incredibly honored but equally flabbergasted because I could not help but wonder if it was in error. I mean, I’m just a pastor of a small congregation in metro Atlanta. However, once the shock of being invited wore off, and after triple-checking the text and email I received confirming that I was indeed asked, a wave of excitement gushed in.

I quickly recognized that this was an extraordinary, perhaps even historical, opportunity in the Asian American Christian context. I may be wrong, but this may have been the first time the White House invited a collective of Asian American Christian leaders for a Listening Session. As selfish as this may sound, I said yes because I wanted to witness and be a part of this historic gathering.

Jason Min: It goes without saying that an invitation to the White House is a huge honor and privilege in and of itself. But what made this particular opportunity even more special was the fact that it was the first time a delegation of explicitly Asian-American Christian leaders gathered to participate in a White House Listening Session.

Growing up as a second-generation Korean American, I spent most of my life doing everything I could to take up as little space as possible. I bought into a Model Minority myth that convinced me that the only way to be accepted by the White majority culture was to essentially remain silent and invisible. Never could I have imagined a scenario in which I as an Asian American— much less an Asian-American pastor—would be invited and empowered to use my voice to represent my community to those at the highest levels of leadership in our country. Needless to say, I was truly humbled and grateful for such an opportunity.

Kevin Yi: About a month before this invitation, I was on a family vacation in Korea, and we had an opportunity to visit the Blue House, which is the Presidential Residence in Seoul. As we were touring the grounds and talking about what a unique opportunity it was to be able to visit the Blue House during our lifetime, we talked about what it would be like to visit the White House in the US. We told the kids that tours of the White House were very rare, and you have to be invited to come to the White House.

And so when the invitation to come to a White House listening session came up, I was very honored and couldn’t help but think about how providential it was as well. I decided on saying yes because, in one sense, maybe my parents will finally be proud of me! (I jest, but only a little.) Really though, I was just honored that anyone would think I have anything to contribute.

And reflecting on my insecurity, I see how pervasive it is for both my wife, Tracy, and I, to think that we have nothing to contribute to important conversations. We have a tendency to downplay our accomplishments, and while that’s certainly culturally motivated, I also think that it’s the result of consistently being looked over and passed over. The invisibility of being Asian American is grafted into the very marrow of my bones sometimes, and so this opportunity gave us some really good opportunities to think about what we would say and how in the end, the AACC has given a voice to so many who feel marginalized. Being seen and being heard is dignifying, and I’m grateful to the White House for giving us the opportunity to do so.

2) What was your experience like?

Peter Lim: I attended a small high school in Cerritos, CA, where I thought I was “pretty smart.” However, my hubris was immediately shattered by my first quarter in university. I encountered countless brilliant people whose academic prowess and acumen eclipsed me. I share this experience because this was how I felt when I met the rest of the delegation assembled by AACC for the White House Listening Session.

Speaking truthfully, I did not fully comprehend what a “White House Listening Session” was. Only after listening to the other amazing people gathered did I recognize that a “Listening Session” was an opportunity to make requests to the White House as representatives of Asian American Christian leaders. Many who comprised this delegation were highly versed and experienced in advocacy work. On the other hand, I had little to no experience in this arena, and upon this realization, “The Imposter Syndrome” sprung up profoundly within me.

Phillip Kim was the representative of the White House, specifically from the Office of Public Engagement, with whom we were able to make our requests. His presence was incredibly disarming, and he exuded a genuine posture of listening. The experience, the expertise, and the eloquence with which the members of our delegation spoke were both remarkable and poignant. As obligatory as this may read, it truly was an honor to simply be in this room, listening to and watching these exceptional advocates do their thing.

Jason Min: This experience was extremely eye-opening for me as it was my first time invited into an explicitly political space as an Asian American pastor. Again, part of the muscle confusion of the conversation in and of itself was the fact that every person in the room was Asian American. We were not a minority voice, but the central voice shaping the discussion.

As someone who is used to being the token Asian guy in the room carrying the burden of representing my entire community in a conversation, it was so freeing to know that I didn’t have to bear that responsibility in this setting and that there were others who could speak on my behalf. More than anything, what I appreciated most about this experience was being able to interact and collaborate with other Asian American Christian leaders and learn about the great work God was doing in their respective communities.

Kevin Yi: Being able to tour the East Wing of the White House and then have a listening session in the White House Conference center was an incredible experience. It’s hard not to be swept up into the ideals and grand history of the United States government. Walking past the portraits of past presidents and being able to see the rooms and dining spaces where truly important conversations have taken place, I couldn’t help but think about the honor of being asked to contribute to this listening session.

When we convened in the conference center to discuss the relevant issues, the contrast between the ideals of our government and how things looked on the ground was stark. The Declaration of Independence states that “all men are created equal,” and yet our experience as Asian Americans throughout US history has shown that to be demonstrably false.

But as there have been many men and women in generations past that fought and endured injustices so that we could enjoy the freedoms that we have now, I was reminded of the early Korean American Church that led the charge to fight for Korea’s independence from under Japanese colonialism. For someone like Dosan Ahn Chang Ho, his faith in Jesus fueled his desire to see his countrymen’s freedom and inherent dignity. I also thought about those Chinese church leaders in San Francisco in the 70s that fought to preserve Chinatown and the Asian American students who protested for AAPI studies on the campus of San Francisco State University. So even though, in many ways, it felt surreal to be in the White House, I was also feeling gratitude for our Asian American Christian forebears who paved the road for us to be here.

3) What were your takeaways from this experience?

Peter Lim: I am still processing this entire experience, but here are two takeaways.

1) There are people within our Asian American Christian communities who are incredibly gifted, talented, and passionate about the work of advocacy. I personally think that it is vital to discover and learn ways in which, as local churches, church leaders, and church members, to empower and unleash these people to do the work of advocacy.

Advocacy may not be something many in the Asian American Church are knowledgeable of or frankly comfortable with. However, I do see it as tangential to the work of the church and a means by which the Gospel can be manifested. Micah 6:8 calls the people of God to “act justly, love mercy, and walk humbly.” Advocacy is “a” way in which biblical justice and flourishing can be realized.

2) A multiprong approach is necessary to address and tackle real issues that exist in our society. Through collaboration, the AACC delegation ultimately presented four requests to the White House: mental health awareness, gun violence prevention, racial solidarity, and inclusion of Asian American history in the K-12 curriculum.

These topics may already be a trigger to some. Regardless of where one stands on these issues, we can all agree that they are massive. Consequently, a multiprong approach is required even to put a dent in these areas.

The government has unique resources and strength to promote justice and flourishing. Advocacy helps keep matters of biblical justice and flourishing relevant and at the forefront of the government. Without the work of advocacy, because of the size and nature of the government, aspects of biblical justice and flourishing will become an afterthought. However, because of the slow-moving nature of government, other avenues must be taken, including non-profits and local churches, in order to address the aforementioned issues.

Jason Min: One of the things I took away from this experience was the need to cultivate more dialogue between Asian American advocacy groups and communities of faith. I think both sides are doing important work but very rarely have opportunities to share their experiences and collaborate with one another. Churches are communal hubs that can mobilize people around specific needs, while advocacy groups can provide the necessary education and action steps to bring about real change in our communities. We definitely need both.

Second, I walked away from this experience with a deep appreciation and gratitude for the work being done by groups like the AACC. One of the things I realized while I was in DC was that there really aren’t many organizations that specifically amplify the voices of Asian Americans in the church and create spaces for such collaborative conversations across denominations, tribes, and networks. Supporting the work of groups like the AACC can create more synergistic opportunities within the Asian American church as a whole.

Third, I definitely walked away with new questions around what it looks like for the church to engage thoughtfully in matters of social policy. Most Asian American churches I’ve been a part of have been fairly apolitical usually because of a fear of being perceived as too political or a general unfamiliarity with navigating topics like these. At least within our community, it’s clear that the younger generation desires to have more of these kinds of conversations in the church and seeks a faith that is more civically engaged.

Kevin Yi: There were a number of takeaways from this experience that I’m continuing to process through. First, what does it mean for us as Asian American Christians to advocate for one another? Are we aware enough about our vast differences and similarities to be able to come together on certain issues to make an impact for future generations? The four issues that we presented to the White House were issues of gun control, AAPI education curriculum, culturally aware mental health resources, and issues of racial solidarity with other minorities.

I continue to work through how as the Asian American church, we can make a difference with these concerns, and which ones are closer to my heart and my ministry context. I am thankful for the organizations like Christians for Social Action, led by Nikki Toyama‑Szeto whose resources have been helpful in thinking about some of these issues. AACC’s continued work in the area of gun control advocacy continues to be on my mind as well.

Second, how is our church community already involved in some of these areas? As I was thinking about the issue surrounding culturally aware mental health, I realized that our church is already involved in this as a community. With the recent discussions around talk therapy not being the best kind of mental health activities for older Asian Americans, I realized that our church’s own Senior College program is designed from the ground up to give the elderly community at our church a dignified space to learn and grow in a communal space. Every year, we do three 8-week “semesters” of a program designed to help the elderly community in our church participate in activities like painting, learning how to use a smartphone, history lessons, civic lessons, sports, and music lessons, led by various members at our church who volunteer their expertise and time. It never occurred to me how good this program is for our senior church members’ mental health. What are the ways that we could see our own church programs and activities through this kind of lens?

4) Are there next steps or suggestions you have for the local Asian American church in these matters?

Peter Lim: As I stated previously, biblical justice and flourishing require a multiprong approach, including the local church. Though the federal, state, or local government has bountiful resources, the local Asian American church equally has its unique role. In fact, in many ways, the Asian American church can do things at a real and practical level that the large systems of government cannot.

The government’s role is to implement systems that will address these issues at the macro level. However, because of the government’s fundamental nature, this will take time, significant time. Consequently, people within our congregations cannot experience any meaningful change or help.

So what can the local Asian American church do? For example, as part of the church’s teaching ministry, a simple thing it can do is teach Asian American and Asian American Christian history. Many in our churches are unaware of the Page Act of 1875, vaguely aware of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, and have a cursory knowledge of the reverberating impact of Executive Order 9066. Concurrently, the church can teach about the effects the 1965 Immigration Act had on the growth of Christianity among Asians in America. As we advocate this type of education to be included in the K-12 curriculum, the local Asian American church can, in the meantime, take it upon itself to be a part of the solution in the meantime.

This type of education can have a significant positive impact on Asian American Christians. First, it will give a sense of grounding, demonstrating that we are not an accident or an outsider in America. Rather, learning our history can help us see the movement and work of God. Furthermore, knowing our history and roots will empower us to fully embrace our identity as God has uniquely formed and molded us.

Jason Min: I believe the Asian American church has an important role and voice in our present cultural moment. Unfortunately, we have often remained silent around the issues that plague our nation, specifically those involving justice. The reasons for this are three-fold:

- Many Asian American churches inherited a theology that over-emphasized individual sin—often at the expense of addressing systemic and structural oppression. Such a theology has produced a general apathy around the real issues impacting our nation.

- Many Asian-American churches bought into the Model Minority myth that trained us to believe that the only way to be accepted in a White-dominant society was to domesticate our voices and be silent. This mindset discouraged our involvement in larger societal issues and was often used to drive a wedge between the AAPI community and other communities of color.

- The dominance of the Black/White perspective has made Asian Americans largely invisible in conversations around race and justice. The fact that this was the first time a delegation of specifically Asian American Christian leaders was gathered at the White House reflects how little the Asian American church has been invited into conversations involving local and national politics.

The Asian American church has to start by naming these dynamics and educating their congregants on AAPI history. We cannot move forward as a people and as a church if we are not aware of the forces that have shaped us. Secondly, the Asian American church must take intentional steps to engage with the city. By tethering ourselves to people different from us to seek the shalom of our city together, we learn to share one another’s burdens and tackle the problems impacting the communities around us as if they are our own.

Kevin Yi: I am continuing to work through how the Asian American church can forge a unique pathway toward social justice engagement. We have to work together for any kind of progress to be made. Though this may seem like an obvious thing to think about, sometimes the problems are so overwhelming it never seems worth it to tackle.

But being exposed to organizations like AACC, Christians for Social Action, Faith and Community Empowerment, and Little Lights, I’m reminded that there are Asian American Christians who are heading incredible organizations that our churches should be partnering with for the sake of the Asian American community. Who else is going to be as deeply concerned about our issues and needs as we are? Rather than seeing one another as competition, how can we join in solidarity, advocacy, and missions with gospel-driven organizations to participate in the activity of generous justice, as the late Tim Keller would say?

The truth is, the generation coming up behind us is watching us. They’re wondering how we will stand in the gap for them, and when we don’t, they’ll just go ahead and march without us, as we’ve seen with the gun control issue. High school students are organizing marches while adults look on. Our children are anxious about the things they hear in the news, and every gun safety drill, though necessary, is stomach-churning for so many of our kids. As church leaders, pastors, and parents, what can we do? “Nothing” is not a viable answer. To think about how we will serve future Asian American generations, we have to work together with other church leaders to set a new, courageous pathway forward.