I once overheard a young woman at the coffee shop table behind me sharing her faith with someone.

“Do you know what the Trinity is?” she asked.

“No.”

“Well, there are three different…parts of God.”

I cringed, bit my lip, and went back to drinking my coffee. Unbeknownst to her, the young lady had made a common mistake for many Christians: She had unwittingly lapsed into heresy while attempting to describe the Trinity.

You may have heard various analogies used to explain the Trinity, such as: “The Trinity is like the three different states of water: liquid, ice, and vapor.” Or maybe you’ve heard that the Trinity is like a three-leaf clover or the different parts of an egg. What many people don’t realize is that most of these analogies (if not all) are akin to the ancient heresies that the early church had dismissed centuries ago.

But if none of these analogies are appropriate to describe God, then what is? Enter the Athanasian Creed.

Trinity In Unity, and Unity In Trinity

The Athanasian Creed was not written by Athanasius, an early Christian who did combat heresies about the Trinity. Although its precise origins are unknown, it has long been recognized as a standard of Christian orthodoxy. It is found in many Protestant confessions: The Book of Concord (Lutheran), the “Thirty-Nine Articles of Religion” (Anglican), and even an early Baptist confession. It is by far the longest and most comprehensive of the ancient creeds, and it can be pretty overwhelming at first glance.

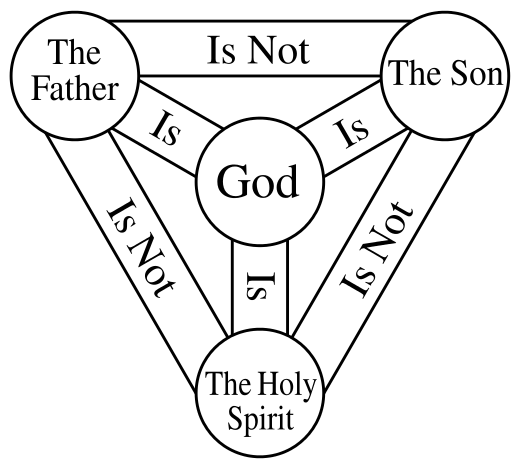

But don’t let its length scare you! The substance of the Athanasian Creed can be summed up in one main idea: “The Father is God, the Son is God, and the Holy Spirit is God. BUT the Father is NOT the Son, the Son is NOT the Spirit, and the Spirit is NOT the Father.” Every line of the Creed’s first half spells this principle out in great detail. A helpful visual that captures this concept is the so-called “Shield of the Trinity.”

One of the earlier lines introduces and captures this idea both beautifully and succinctly: “We worship one God in Trinity, and Trinity in Unity; neither confusing the Persons, nor dividing the Essence.”

“Confusing the Persons?”

The Creed reminds us that we must not confuse the Father with the Son, the Son with the Spirit, or the Spirit with the Father. That would be to commit the heresy of modalism.

Modalism was an ancient heresy that claimed that God is only one person who “shows up” as the Father, Son, and Spirit — somewhat like an actor wearing different masks. The famous (or infamous ) “God is like three states of water” analogy falls into this category. But the early church quickly realized that in Scripture, God is not just one person.

For example, the early church recognized that when Jesus is baptized in Scripture, the Father blesses him, and the Spirit falls upon him (Matthew 3:13-17). Jesus prays to the Father (Matthew 26:39) and even cries out to him (Matthew 27:46). He promises to send the Spirit, described as “another Advocate,” who comes from the Father (John 14:16). There is a distinctiveness between each Person of the Trinity.

Modalism is a common error. I know I unknowingly espoused modalism until college, when I was gently but promptly corrected by an older, wiser Christian. For example, some Christians will pray, “Dear Father, thank you for dying for us on the cross…” But it was the Son that died on the cross, not the Father!

“Dividing the Essence?”

The Creed also reminds us that we must not “divide the Essence,” which is saying that there are parts to God. That would be to commit the error of partialism. The three-leaf clover or egg analogy falls in this category. Instead, all three Persons are simultaneously and equally (albeit mysteriously) the one, true God. That is, all three Persons of the Trinity share the same qualities, attributes, characteristics, and “essence” that makes each of them God: uncreated, unlimited, eternal, infinite, almighty, etc. The Creed goes on to say that their glory is equal and their majesty co-eternal.

For example, in Matthew 28:19, we are told that each Person shares the same divine name (which was treated with the utmost reverence by Jews). We know all the fullness of God dwells in Jesus (Colossians 2:9). And we know that both the Son and the Spirit share in the same title as “Lord” (Philippians 2:5-11, 2 Cor. 3:16-17) and are worthy of worship.

Thus, to say that any Person of the Trinity is only a “part of God” is to say that he is only “part God.” But Scripture attests that each Person is fully God in himself.

“Not three Gods, but one God…”

Finally, if it wasn’t obvious enough, the Athanasian Creed goes at length to make it clear that — in agreement with Deuteronomy 6:4 — there is only one God:

““So the Father is God; the Son is God; and the Holy Ghost is God. And yet they are not three Gods; but one God. So likewise the Father is Lord; the Son Lord; and the Holy Ghost Lord. And yet not three Lords; but one Lord. [We] acknowledge every Person by himself to be God and Lord; So are we forbidden by the *catholic religion; to say, There are three Gods, or three Lords.”

We must acknowledge God’s “oneness” as much as his “threeness.” A verse that paints this beautifully is John 1:1 — “The Word was with God and the Word was God.” The preexistent Word was simultaneously God and “with God.”

So What?

My favorite hymn growing up was “Holy, Holy, Holy,” which sings, “God in three Persons— blessed Trinity.” To this day, a sense of awe, wonder, and mystery envelopes me as I hear those words. It’s because we worship a God who transcends our comprehension and understanding. Jesus says in John 17:3 that eternal life is to know the one true God, and knowing God entails knowing about him. The creeds give us the language to speak about God accurately, and in doing so, they allow us to know him more intimately.

Notice what the Athanasian Creed doesn’t do. It does not try to explain the Trinity (like so many of our analogies do). It simply aims to describe the Trinity by giving us the proper vocabulary to use. It merely tells us what we can or cannot say when talking about God. Try picturing the shield of the Trinity as a platform that you are walking on: Anything outside of it is out of bounds, and if you step off, you will fall into the slimy vat of heresy.

The early church was not trying to be novel. They weren’t trying to be more creative than Scripture. They described what they recognized in Scripture as truth, and were content to leave it at that. We would be wise to follow in their footsteps. So the next time you or someone else wants to give an analogy for the Trinity, consider using the language that the church has used for centuries.

And finally, instead of regarding the Trinity as alien territory reserved for ivory-tower theologians to explore, consider the words of an early 17th century Baptist confession: “…and we worship and adore a Trinity in Unity; and a Unity in Trinity, three Persons, and but one God; which Doctrine of the Trinity, is the foundation of all our Communion with God, and comfortable Dependence on him.” Amen.

The following is the text of the Athanasian Creed:

Whoever desires to be saved should above all hold to the catholic faith. Anyone who does not keep it whole and unbroken will doubtless perish eternally. Now this is the catholic* faith:

That we worship one God in Trinity and the Trinity in unity,

neither blending their persons

nor dividing their essence.

For the Person of the Father is a distinct person,

the Person of the Son is another,

and that of the Holy Spirit still another.

But the divinity of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit is one,

their glory equal, their majesty co-eternal.

What quality the Father has, the Son has, and the Holy Spirit has.

The Father is uncreated, the Son is uncreated, the Holy Spirit is uncreated.

The Father is immeasurable, the Son is immeasurable, the Holy Spirit is immeasurable.

The Father is eternal, the Son is eternal, the Holy Spirit is eternal.

And yet there are not three eternal beings; there is but one eternal being.

So too there are not three uncreated or immeasurable beings;

there is but one uncreated and immeasurable being.

Similarly, the Father is almighty, the Son is almighty, the Holy Spirit is almighty.

Yet there are not three almighty beings; there is but one almighty being.

Thus the Father is God, the Son is God, the Holy Spirit is God.

Yet there are not three gods; there is but one God.

Thus the Father is Lord, the Son is Lord, the Holy Spirit is Lord.

Yet there are not three lords; there is but one Lord.

Just as Christian truth compels us to confess each Person individually as both God and Lord,

so catholic religion forbids us to say that there are three gods or lords.

The Father was neither made nor created nor begotten from anyone.

the Son was neither made nor created;

he was begotten from the Father alone.

The Holy Spirit was neither made nor created nor begotten; he proceeds from the Father and the Son.

Accordingly there is one Father, not three fathers;

there is one Son, not three sons;

there is one Holy Spirit, not three holy spirits.

Nothing in this Trinity is before or after,

nothing is greater or smaller;

in their entirety the three persons

are co-eternal and coequal with each other.

So in everything, as was said earlier,

we must worship their Trinity in their unity

and their unity in their Trinity.

Anyone then who desires to be saved

should think thus about the Trinity.

it is necessary for eternal salvation

that one also believe in the incarnation

of our Lord Jesus Christ faithfully.

Now this is the true faith:

That we believe and confess

that our Lord Jesus Christ, God’s Son,

is both God and human, equally.

He is God from the essence of the Father,

begotten before time;

and he is human from the essence of his mother,

born in time;

completely God, completely human,

with a rational soul and human flesh;

equal to the Father as regards divinity,

less than the Father as regards humanity.

Although he is God and human,

yet Christ is not two, but one.

He is one, however,

not by his divinity being turned into flesh,

but by God’s taking humanity to himself.

He is one,

certainly not by the blending of his essence,

but by the unity of his Person.

For just as one human is both rational soul and flesh,

so too the one Christ is both God and human.

He suffered for our salvation;

he descended to hell;

he arose from the dead;

he ascended to heaven;

he is seated at the Father’s right hand;

from there he will come to judge the living and the dead.

At his coming all people will arise bodily

and give an accounting of their own deeds.

Those who have done good will enter eternal life,

and those who have done evil will enter eternal fire.

This is the catholic faith:

one cannot be saved without believing it firmly and faithfully.

* “Catholic” here means “universal,” not “Roman Catholic”